Fireworks have come a long way since they were first invented in ancient China. As early as 200 BC, people had found that they could create loud bangs by throwing bamboo shoots into a fire; when heated, the air pockets inside the plant expand rapidly and the bamboo explodes with a violent crack. But it wasn’t until after the Chinese invented early forms of gunpowder around the 7th century that fireworks really took off—literally as well as figuratively. Global trade with China over the next 1,000 years brought polytechnic science to the Middle East, Europe, and the New World; any large public celebration, from a royal coronation to religious holidays, featured a fireworks display as its grand finale. America’s Fourth of July fireworks tradition began with its very first Independence Day in 1777.

Fireworks have come a long way since they were first invented in ancient China. As early as 200 BC, people had found that they could create loud bangs by throwing bamboo shoots into a fire; when heated, the air pockets inside the plant expand rapidly and the bamboo explodes with a violent crack. But it wasn’t until after the Chinese invented early forms of gunpowder around the 7th century that fireworks really took off—literally as well as figuratively. Global trade with China over the next 1,000 years brought polytechnic science to the Middle East, Europe, and the New World; any large public celebration, from a royal coronation to religious holidays, featured a fireworks display as its grand finale. America’s Fourth of July fireworks tradition began with its very first Independence Day in 1777.

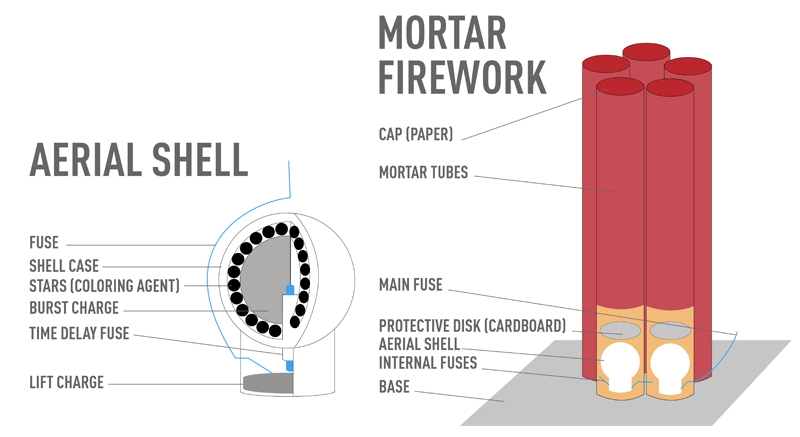

Fourth of July-style fireworks pack incredibly explosive power inside paper-wrapped bundles called shells, which contain all of the materials for a dazzling light display. If you cut a shell in half lengthwise, you’d see a time fuse at its center, connecting to a packet of gunpowder at the shell’s base called the lift charge. Lighting the fuse ultimately ignites the lift charge, propelling the shell into the air. The time delay fuse, ignited by that initial blast, continues to burn through various breakpoints that set off the actual fireworks. A core of gunpowder, dubbed the burst charge, surrounds the time fuse. Mingling within the burst charge are pea-sized balls called stars, which mix color-producing compounds and chemicals to create a shower of colored sparks.

Without its stars, fireworks would just look like puffs of yellowish embers. These tiny pellets contain an array of chemical compounds to make rich colors, plus doses of gunpowder to vary the heat and duration of the burst. Stars also contain an oxidizing agent, such as potassium nitrate, which produces oxygen to fuel the explosion. A binding medium like dextrin ties all the elements together. When a shell is ignited, the heat causes electrons in the color-producing compounds to get “excited” and become unstable. The electrons quickly return to their original energy levels, emitting the excess energy as colored light. Compounds of strontium give off red light; calcium compounds, orange; copper compounds, blue; barium or boron compounds, green; and sodium compounds, bright yellow. Combinations of chemicals create shades—strontium plus copper results in violet, calcium, and barium emit yellow. Heat is also a factor: superheating magnesium or aluminum filings in the stars will create a silver burst, while burning magnesium, aluminum or titanium shards produces white light.

The shapes you see in the sky depend on the arrangement of the stars inside the shells. A symmetrical circle configuration, for instance, will explode into a ring in the air. Poetically named patterns like willow, chrysanthemum, palm, roundel and serpentine require complicated arrangements of stars within the burst charges, an art that takes years to master. Multibreak shells—several shells with stars of different colors and designs in a single package—rapidly explode in sequence. The audience, though, sees only a single firework that appears to change shape, such as a round sphere (the first shell), with a star shape in its center (the second shell).

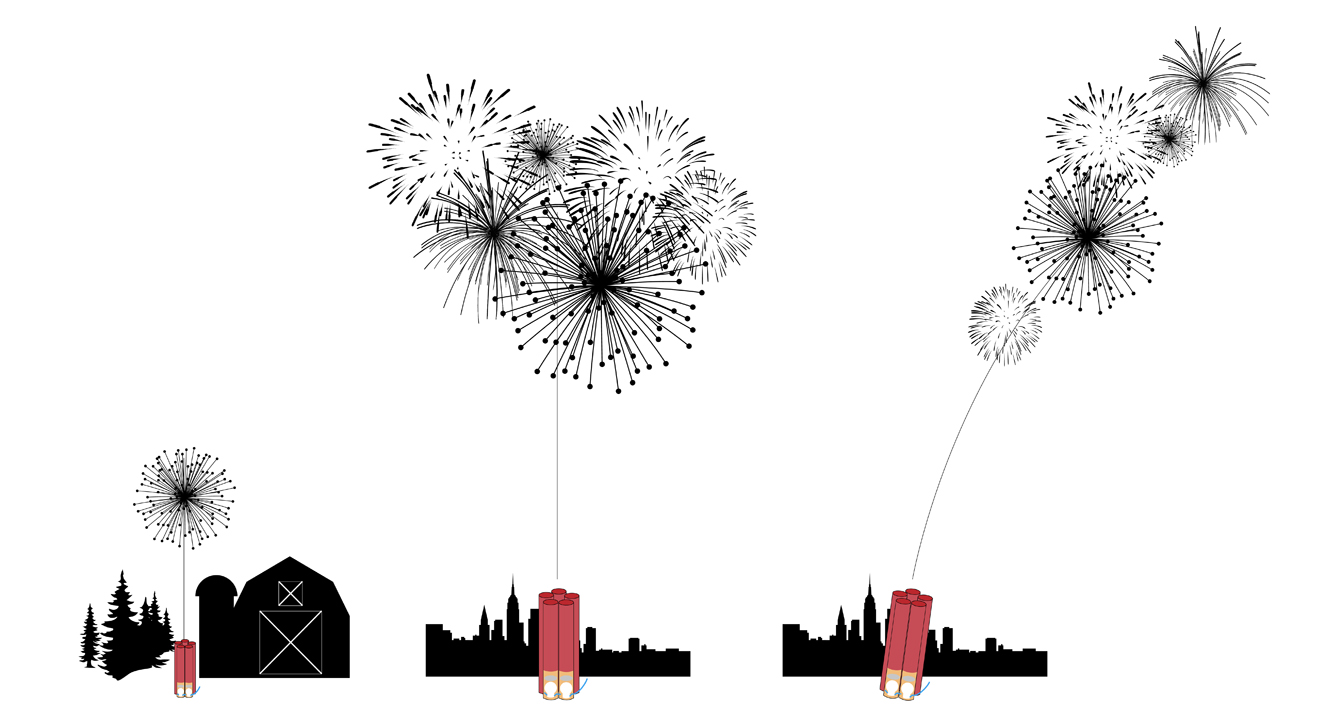

Most Fourth of July displays use fireworks shot out of short steel tubes, called mortars, planted in the ground. Each mortar stands straight up, and its diameter matches the diameter of the shell it will launch. When the shell’s fuse is lit, the mortar “steers” it on a purely vertical trajectory to its desired altitude. The rule of thumb holds that the shell will rise 100 feet for every inch of its diameter; so a 10-inch shell will rise to 1,000 feet, the typical height for big city Fourth of July extravaganzas. Small-town fireworks displays will typically use smaller shells, about 3-4 inches in diameter, which will sail up to 300-400 feet in altitude. Timing is everything: fireworks designers make sure the shell explodes at the precise moment that it reaches maximum altitude by implanting the correct length of time fuse inside the shell. Don’t try this at home! Consumer fireworks, though they may seem mostly benign, caused over 13,000 injuries last year. “Oohing” and “aahing” at your local professional Fourth of July celebration is the safest way to enjoy chemistry in action.

Comments

Trackbacks

[…] is an explanation of the science behind the beauty of fourth of July […]