Articles

An image of Euler’s Equation, widely regarded as one of the most elegant in mathematics. Courtesy of Borkur.net Bertrand Russell, in his book Mysticism and Logic (1918), wrote, “Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty—a beauty cold and austere, like that of sculpture, without appeal to any part of our weaker nature, without the gorgeous trappings of painting or music, yet sublimely pure, and capable of a stern perfection such as only the greatest art can show.” The first truly beautiful thing I encountered in mathematics was calculus. It was love at first sight, and I have been a mathematician ever since. Beauty is one of the last things most calculus students associate with the subject. That’s hardly surprising. It is generally presented as a utility—a collection of techniques for solving problems to do with continuous change (in the case of differential calculus) or the computation of areas and volumes (for integral calculus). Moreover, such is the power of this toolbox, and so radically different are its techniques from anything the student has previously encountered in mathematics, that it takes the calculus novice every bit of effort and concentration simply to learn and follow the rules. …

Read MoreScience communication is difficult. It can be crippled by the complexity of its own subject matter. It can be steeped in jargon, too dense for its readership, or, conversely, too simplistic to satisfy its critics in the scientific community. It can lack warmth, or be too paranoid about its empirical rigor to engage in the metaphoric flights—the quick shifts from microcosm to macrocosm—that cue readers to an emotional engagement in any subject. The problem may lie in an inescapable tautology: to fully understand a scientific, taxonomic, objective conception of the natural world is to be so steeped in scientific idiom that poetics become impossible. And yet, there are those who are capable of communicating the invisible phenomena of science to the public. These people are essentially bilingual. The Sagans, the deGrasse Tysons, the E.O Wilsons; Angier, Attenborough, Carson and Greene; the radio producers, writers, filmmakers, documentarians, and public speakers; these are our human bridges, our storytellers, fluent in both big and small. It’s a specific skill, to be a gifted science communicator—that rare person who can straddle two divergent worlds without slipping into the valley between the so-called “Two Cultures,” someone with hard facts in their mind and literary gems …

Read MoreThe air grows thick. Dark clouds churn like a pot of boiling water overhead. The colors of reality become oversaturated—greens too green, yellow a sickly gold. This is what tornado weather looks like, and the United States has been hit with a lot of it lately.

Read MoreLise Meitner and Otto Hahn. She the physicist and he the chemist; her creative, theoretical models and analyses based on his exacting chemical evidence; a perfect pair of scientific thinkers. Meitner’s reputation soared with the couple’s co-discovery of an isotope of protactinium, element 91, and her legacy seemed assured. She was the second woman to receive a doctoral degree from the University of Vienna, and then a prestigious faculty appointment. She gained recognition from early twentieth century luminous Berlin physicists including Max Planck, and from Albert Einstein, who hailed her as “our Marie Curie.” Born into a Jewish family in Vienna, Meitner’s tragic exclusion from history began with her exile from Germany following the Nazi invasion of Austria, despite her conversion to Protestantism years before. Though geographically separated from Hahn, she continued to develop the theoretical model of the process from Stockholm, through correspondence and a secret meeting in Copenhagen. Yet in 1939, the chemical evidence of nuclear fission—the halving of atomic nuclei—was published in Nature only under the authorship of Hahn and additional collaborator Fritz Strassman, leading to Hahn’s sole Nobel Prize for the discovery. Meitner’s direction of these experiments, and subsequent physical explanation and naming of the …

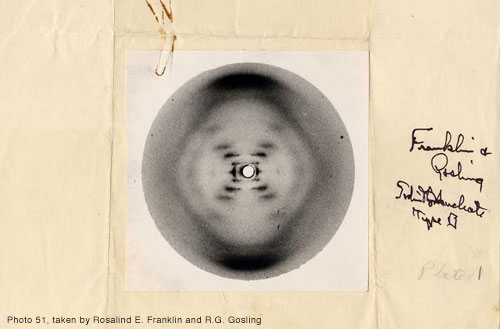

Read MoreThe mysterious story of molecular biologist Rosalind Franklin will be explored next week at the World Science Festival’s The Secret Behind the Secret of Life: Facts and Fictions with The Ensemble Studio Theatre Production of Anna Ziegler’s Photograph 51. The photo itself has been hailed by the British scientific icon and expert x-ray crystallographer John Bernal as “the most beautiful x-ray photograph of any substance ever taken.” But the photographer, Rosalind Franklin, The Dark Lady of DNA, has remained a cipher.

Read MoreYou slam your hand in a door, and the experience becomes etched into your brain. You carry a memory of the swinging panel, the sound as it crushes your flesh and the shooting pain as your skin gives way. Your body remembers it too. For days afterwards, the neurons in your spine carry pain signals more easily form your hand to your brain. As a result, your hand feels more sensitive, and even the lightest touch will trigger an unpleasant reaction. It’s as if your spine carries a memory for pain. This is more than a metaphor. Two groups of scientists have found that one special molecule underlies both processes. It helps to store memories in our brains, and it sensitises neurons in our spines after a painful experience. It’s a protein called PKMzeta. It’s the engine of memory. When we learn new things, PKMzeta shows up at the gaps between neurons (synapses) and strengthens the connections between them. These bolstered synapses are the physical embodiment of our memories, and they are fragile things. It turns out that we need to continually recreate PKMzeta at synapses to keep our memories alive. If the protein disappears, so do our memories. Unlike …

Read More