Articles

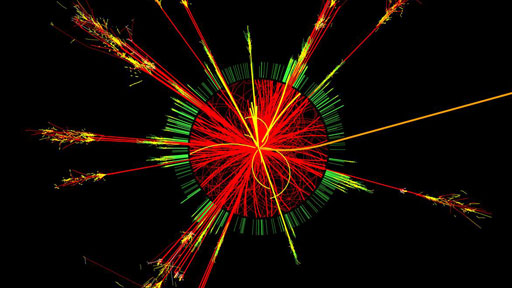

This morning, the New York Times published an op-ed piece by WSF co-founder and theoretical physicist Brian Greene. In it, he explains the origins of the now famous Higgs boson, and Peter Higgs, who hypothesized its existence in 1964. The emptiest of empty space, vacuumed clean of matter and radiation, would still be permeated by the Higgs field. Higgs thus suggested a rewriting of the very definition of nothingness, filling otherwise empty space with a substance capable of bestowing upon particles their mass. Nearly 50 years later, CERN made the announcement that they may have found traces of the Higgs. The announcement has physicists all over the world on the edge of their seats; waiting with equal anticipation to hear whether the Higgs can be confirmed or not. While the official line is, rightly, one of cautious optimism, the excitement, especially behind closed doors, is palpable. Read the entire essay in today’s New York Times Brian also appeared on CNN to talk about the December 13th CERN Announcement. Watch now Editor’s Note: Please forgive the multiple references to the “God Particle”

Read MoreRecently, World Science Festival co-founder Brian Greene appeared on Last Call’s Spotlight series. They were kind enough to post the clip online, and we’ve embedded it here for you. During the interview, Brian talks about his recent NOVA series, The Fabric of the Cosmos, which aired last month, how his father’s approach to music mirrors his own outlook on mathematics, and his views on popularizing science for the general public. For more about NOVA’s Fabric of the Cosmos, you can watch clips and full episodes here » Check out the 2011 blog series, Ask Brian Greene.

Read MoreBrian Greene continues the WSF Live Forum all month long. Each day, he’ll answer one of your questions for this ongoing series that delves into the fundamental nature of space, time, and reality as we may or may not know it. If you traveled through a wormhole to an earlier time, would your presence create a “new” version of that earlier time or would it be the “original” version of that time? — via physicsforums.com First, bear in mind that while the notion of a wormhole finds a natural place in the mathematics of Einstein’s general relativity, there is no experimental or observational evidence that wormholes exist. Moreover, even if they did exist, it is unclear whether one could generate a macroscopic wormhole and keep it open, allowing a human to safely travel through it. So, you should consider the whole collection of ideas that includes wormholes and time travel as highly speculative. OK. Let’s speculate. If you did have a wormhole—a tunnel from one location in space to another—hen it’s pretty clear how to turn it into a time machine: move the openings of the wormhole relative to one another (so that time at the two openings elapses at …

Read MoreBrian Greene continues the WSF Live Forum all month long. Each day, he’ll answer one of your questions for this ongoing series that delves into the fundamental nature of space, time, and reality as we may or may not know it. Today, Brian Greene considers two related questions: If the universe is expanding, is it theoretically not infinite? In other words, if the universe is infinite, how can it be a discrete thing that is expanding? And if it is not infinite, is space infinite? Or does “space” only exist inside the universe, and not beyond? —Michael Pick, New York, NY It is a truly awesome concept that the universe is expanding. But what is it expanding into? Into what “space” is it expanding and what happens to that “space” when the universe contracts/has contracted? —Andrea We don’t know whether the universe is finite or infinite. But in either case, the concept of “space expanding” raises basic questions: (a) what’s the universe expanding “into”? and (b) if the universe is in fact infinite, how can it expand as it seemingly can’t grow larger than the infinite size it already has? Let me address both. (a) When we speak of space …

Read MoreBrian Greene continues the WSF Live Forum all month long. Each day, he’ll answer one of your questions for this ongoing series that delves into the fundamental nature of space, time, and reality as we may or may not know it. Why are so many physicists chasing string theory when, after 30+ years, there is still no means of testing it? —C Gulow (via BoingBoing) The primary goal of string theory is to join the laws of quantum mechanics (the laws of the “small”) with the laws of general relativity (the laws of the “large”), into a single mathematically consistent framework. This is vital because in the standard formulation (without string theory, say), the union of quantum mechanics and general relativity leads to mathematical inconsistencies, sort of like what happens on a calculator if you divide 1 by 0. And since the universe is surely consistent, we need a mathematical description that’s consistent too. Without such a consistent formulation, for example, we don’t stand a chance of fully understanding the origin of the universe or what happens in the deep interior of black holes. Melding quantum mechanics and general relativity is a tough nut to crack; to date, very few …

Read MoreBrian Greene continues the WSF Live Forum all month long. Each day, he’ll answer one of your questions for this ongoing 2011 series that delves into the fundamental nature of space, time, and reality as we may or may not know it. Brian, what was the driving force that made you who you are as a physicist? My intended major is physics, and it can become weird at times as much as I love it. What do you recommend me to do while I attend a community college? I really want to become a famous physicist like you with my passion for physics. —Kenneth Rosario-Gonzalez, Tampa, Florida There were two forces that drove me to physics. The first was a love of numbers. When early on my dad taught me the basics of arithmetic, I was amazed that with just paper and pencil you could endlessly do new things. I remember when I was about 5, I’d tape together many large sheets of construction paper on which I’d spend days multiplying two 30 digit numbers. I found it captivating to do a calculation that, more than likely, no one had ever done before. And with good reason—the calculation wasn’t particularly …

Read More