Articles

The modern era has already seen a measureable uptick in certain areas of brainpower. Since the 1930s, standardized test scores have been steadily increasing, a phenomenon called the Flynn Effect. You might assume that the rise in IQ scores is due to people doing better on basic math skills and memorizations—basically, anything we can study for. But what’s especially interesting about the Flynn Effect is that the opposite seems to be true: Humanity’s biggest improvements have been in abstract thinking and general cognitive functioning. One standard intelligence test is Raven’s Progressive Matrices, developed by English psychologist John C. Raven in 1936. The test is a series of 60 non-verbal multiple-choice questions that’s ideal for measuring abstract reasoning. A test-taker is shown a series of patterns in a 3×3 grid, with one picture missing; the person has to pick the right pattern out from multiple choices. It’s not the kind of test you can easily cram for.

Read MoreOn what would have been her 215th birthday, famed British fossil collector Mary Anning has been bestowed with that imprimatur of geeky glory: a Google Doodle, depicting her uncovering yet another ancient specimen. Anning grew up in Lyme Regis, a town in southwestern England; millions of years ago, that same land once lay near the equator, covered by a tropical sea. It is a perfect breeding ground for fossils, formed after marine creatures large and small died and were buried in the mud on the seafloor. Her carpenter father, Richard Anning, was also a fossil collector and passed this skill onto his daughter. After Richard died in 1810, the Anning family was on the cusp of abject poverty until they got into the fossil-hunting business full-time. Though Anning is sometimes credited as the discoverer of the first ichthyosaur fossil, this isn’t true. But the Ichthyosaurus she did discover around 1810 (when she was about 11 years old) was the first specimen to attract major attention in England; the ancient seagoing reptile’s remains were eventually bought by the British Museum. Anning also unearthed the first pterosaur found in England, the first nearly complete plesiosaur, and a host of other natural curiosities, including a …

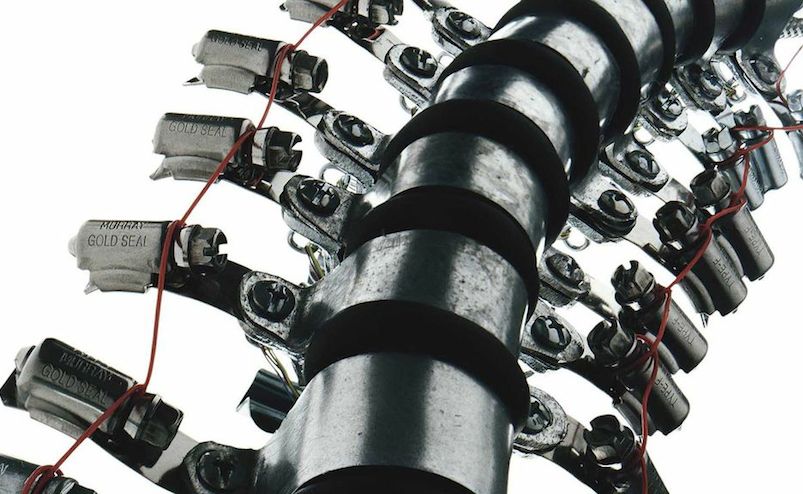

Read MoreThe line separating human from machine got a bit fuzzier last month, when Google finalized two patents for smart contact lenses designed to alert people with diabetes to potentially dangerous dips in blood sugar levels. Around the same time, scientists at the University of Louisville helped three people with complete lower limb paralysis move their legs and feet by stimulating electronic devices they’d embedded in their spinal cords. And earlier this year, doctors implanted a chip in the brain of a man with complete paralysis that allowed him to move objects with his mind with the help of a prosthesis.

Read More

Michael Bay shows equal contempt for the laws of physics and the laws of storytelling in Armageddon. This 1998 overcooked disaster movie is so stuffed with physical impossibilities that NASA experts voted it one of the most scientifically flawed films ever made (though the top dishonor went to the 2009 disaster film 2012).

Read More

In Audrey Niffenegger’s novel “The Time Traveler’s Wife,” Henry DeTamble is a man with a rare disorder that causes him to involuntarily travel through time. His wife Clare experiences life linearly, but never knows when or where she will see her husband next. “Each moment that I wait feels like a year,” Clare says. “Through each moment I can see infinite moments lined up, waiting.” You don’t need a time-traveling husband to have a warped experience of time like Clare’s—think of how long a Monday back at work seems to stretch out, and how quickly the weekend flashes by. Time should march steadily, but that doesn’t always match our perception. Neuroscientists and psychologists are searching for answers to this conundrum, using psychophysical experiments and brain scanning technology to unlock just how human brains track the passage of time. Researchers are gaining insights, and some of these findings could help us to better understand, among other things, disorders like schizophrenia and Parkinson’s where sufferers have trouble perceiving time.

Read MoreFifteen years ago, the promise of gene therapy was dealt a stunning blow by the widely reported death of eighteen-year-old Jesse Gelsinger during a clinical trial. Researchers were attempting to cure Gelsinger and other patients suffering from a rare condition called ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, which leaves people unable to process nitrogen in their blood—making protein-rich foods potentially deadly. To treat Gelsinger, scientists injected him with a virus engineered to include a functional version of the gene that was faulty in OTCD patients. But within 48 hours, Gelsinger’s condition dived dramatically; his body swelled, his skin and eyes yellowed, showing signs of liver damage, and his fever spiked dangerously high. Four days after injection, doctors found Gelsinger had no hope of recovery, and his family decided to take him off of life support.

Read More