After Sara Lazar suffered a running injury in the 1990s, she decided to take up yoga and meditation. She remembers rolling her eyes whenever the teacher touted the supposed benefits of yoga: stress relief, a reduction in symptoms associated with depression and insomnia, and a happier and higher quality of life. After a few weeks though, Lazar’s outlook changed. “I started noticing that I was calmer and I was better able to handle difficult situations… and I was feeling more compassionate and open-hearted towards other people,” she said in a 2011 talk at TEDx Cambridge. Lazar, who was a Ph. D student in molecular science at the time of her injury, decided to change her career focus to study the neuroscience of meditation.

After Sara Lazar suffered a running injury in the 1990s, she decided to take up yoga and meditation. She remembers rolling her eyes whenever the teacher touted the supposed benefits of yoga: stress relief, a reduction in symptoms associated with depression and insomnia, and a happier and higher quality of life. After a few weeks though, Lazar’s outlook changed. “I started noticing that I was calmer and I was better able to handle difficult situations… and I was feeling more compassionate and open-hearted towards other people,” she said in a 2011 talk at TEDx Cambridge. Lazar, who was a Ph. D student in molecular science at the time of her injury, decided to change her career focus to study the neuroscience of meditation.

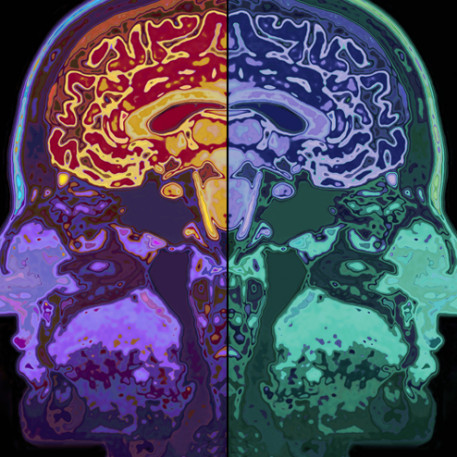

Now Lazar is one of a growing number of researchers who are using Magnetic Resonance Imaging—a medical technique that uses a magnetic field and radio waves to peer inside the body—to see how meditation may mold the brain.

Starting in the 1970s, scientists began to understand neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to rewire connections between neurons based on changes in behavior and environment. Now there’s a growing body of MRI data indicating that meditation helps strengthen specific areas of the brain that help reduce stress, increase attention and memory, and boost immune function.

In a study published in the journal Neuroreport, her team used MRI to compare the brains of 20 long-term meditators with 15 non-meditators. The meditators had increased thickness in regions of the brain involved with attention and sensory processing. The pre-frontal cortex, a part of the brain that shrinks with age, was also thicker in older meditators, suggesting that it could help delay the aging process.

The study could not confirm if the brain changes were a direct result of meditation, though. To this end, Lazar’s research group took MRI of the brains of 16 volunteers before and after they participated in an 8-week mindfulness meditation class. MRI scans taken of the meditators after the class showed that the hippocampus, important for learning and memory, had grown thicker, with a higher concentration of gray matter. Scans also showed decreased gray matter in the amygdala, a part of the brain that plays a role in anxiety and stress. None of these changes were present in the control group, Lazar’s team reported in the journal Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging.

Meditation may have benefits beyond the brain as well. A 3-month long study conducted on more than 100 patients with high blood pressure at Massachusetts General Hospital found that meditation significantly reduced blood pressure levels. Participants were randomly assigned to two groups: Half received weekly counseling sessions and recommendations on health and fitness, while the remainder attended sessions on relaxation and meditation in addition to the counseling that the first group received. After 20 weeks, both groups showed reductions in blood pressure, and two-thirds of the patients attempted to reduce their anti-hypertension medication. Of the participants that received additional sessions on relaxation, 32 percent maintained lower levels of blood pressure even after eliminating one or more medications. The researchers think this benefit may be due to the fact that relaxation increases nitric oxide, a gas that is produced in the body and is known to dilate blood vessels.

In another study, published in Psychoneuroendocrinology, University of Wisconsin-Madison psychiatrist Richard Davidson found that meditation could affect genes linked to immune function. A group of 19 experienced meditators practiced mindfulness meditation for eight hours while a control group of 21 engaged in non-meditative activities. Blood samples taken from all study participants before and after the eight hours showed that the experienced meditators had reduced expression levels of genes related to inflammation. A decrease in gene products involved in inflammation relates to a quicker recovery time from stressful events.

Davidson has also developed a Kindness Curriculum (KC) for preschoolers, which uses relaxation techniques such as breathing practice to help kids calm their minds, and provides them with lessons and activities to improve attention and compassion. Preliminary data showed children that participated in 8 or 12-week KC groups performed better on computer tests that measured attention. When children were given the option of keeping stickers for themselves or sharing them with a child they were told was sick, the KC kids were more willing to share.

“I’m convinced that loving kindness or compassion meditation can actually cultivate improved social sensitivity and kindness,” Davidson says.

While researchers agree that meditation has a plethora of benefits, Lazar cautions, “It is not a cure-all.” There is still a lot we don’t know, and scientists are finding that different forms of meditation can produce different effects on the mind.

In a recent study published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, a team led by University of Oslo researcher Svend Davanger placed 14 meditators in fMRI machines to measure brain activity during two different kinds of meditation: Acem meditation, a form of relaxation where practitioners focus on repeating a word while allowing fleeting thoughts to pass through the brain, or direct meditation with a controlled focus on breathing, without fleeting thoughts. Surprisingly, researchers found that in subjects practicing Acem meditation, there was greater activity in the default mode network of the brain, which processes memories and emotions. This is an interesting result in the light of the conventional wisdom of meditation; most mindfulness meditation schools consider mind wandering (as allowed in Acem) to promote anxiety and depression.

Although there is still a lot to learn about how all of the different kinds of meditation affect the body and mind, one thing is clear: Meditation can provide an oasis of calm amid the chaos of the world, and science is one way to understand the mechanism by which we can change ourselves to meet the chaos.

“Our brain is not programmed from birth to live the way that we do,” Davanger says. “It has to make sense of all the different experiences we make in order for us to live sensible and fruitful lives in the time ahead.”

Photo Credit: iStockphoto/MachineHeadz

Comments

Trackbacks

[…] are the worst offenders. * 10 Ways Television Has Changed the Way We Talk. * Enlightened Neurons: Can Meditation Beef Up Brain Regions? Research shows physical changes in the brain after meditation training. * 13 ways to make your ice […]