Your dog looks guilty and sorry, but is she? And what’s going on with other puppy dog looks?

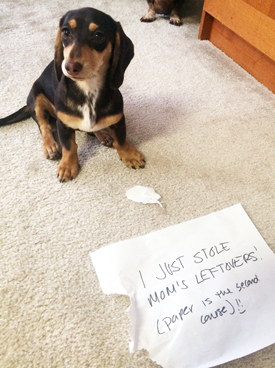

Shaming on the Internet keeps getting more and more creative, and its targets more diverse. Witness the hangdogs of the website dogshaming.com who bear placards outlining their offenses ranging from “I ate Josh’s underpants. I feel no remorse!” to “I get soooo excited when we have company over that I hump the cat!” In a majority of the doggie mug shots, the pooch looks up at the camera or slightly off to the side as if wordlessly apologizing to their aggrieved owners.

While the dogs of Dog Shaming might look contrite, they probably don’t actually feel guilty. Behaviorists who study man’s best friends say that when you admonish a dog, the response of laid-back ears, cowering posture, and droopy eyes isn’t connected to the shameful behavior.

Barnard College psychologist Alexandra Horowitz has investigated shame-faced dogs in experiments where dogs are told not to eat treats, then left alone, and ultimately either admonished or ignored by their owners regardless of whether or not they obeyed or disobeyed. She found that a dog’s guilty look “appeared most often when owners scolded their dogs, regardless of whether the dog had disobeyed or did something for which they might or should feel guilty,” Horowitz told The Associated Press. “It wasn’t ‘guilt’ but a reaction to the owner that prompted the look.” (She added that dogs might actually feel guilt but that that look is not about that, and noted the difference between guilt and shame.)

Barnard College psychologist Alexandra Horowitz has investigated shame-faced dogs in experiments where dogs are told not to eat treats, then left alone, and ultimately either admonished or ignored by their owners regardless of whether or not they obeyed or disobeyed. She found that a dog’s guilty look “appeared most often when owners scolded their dogs, regardless of whether the dog had disobeyed or did something for which they might or should feel guilty,” Horowitz told The Associated Press. “It wasn’t ‘guilt’ but a reaction to the owner that prompted the look.” (She added that dogs might actually feel guilt but that that look is not about that, and noted the difference between guilt and shame.)

However, this doesn’t mean that a dog’s look is totally meaningless. Domesticated dogs are intimately dependent on humans. Meanwhile, we have eyes that are designed to be seen as well as to see, with a high contrast between colored iris and white sclera, which itself contrasts with the skin of the face. Even human infants can pick up cues from the eyes far more readily than adult apes. Perhaps throughout their domestication dogs learned the importance of eyes as windows to the souls—or, at least, the bonding instincts—of their owners?

New research published in the journal Science this week suggests that, indeed, dogs have found a way to co-opt the meaningfulness of the human gaze. Scientists from Azabu University, the University of Tokyo Health Sciences, and Jichi Medical University in Japan have found that there is some measurable effect to be found in eye contact between dogs and people.

In their experiments, Miho Nagasawa and colleagues measured concentrations of the molecule oxytocin, a hormone thought to be central to bonding and other social behaviors, in the urine of dogs and their owners before and after they spent some time making eye contact with each other. They found that both dogs and humans had increased levels of oxytocin after maintaining eye contact, and that levels increased with the length of the mutual gazing. When the experiment was conducted with tame wolves and their owners, the wolves “rarely” maintained eye contact with the humans, and there was no observable effect of gazing on oxytocin ratios. In a follow-up experiment, the team found that administering oxytocin to dogs made them look at their owners longer but only in female dogs.

The results support the idea that there is “a self-perpetuating oxytocin-mediated positive loop in human-dog relationships that is similar to that of human mother-infant relations,” the team wrote. For both parties, locking eyes “brought on social rewarding effects due to oxytocin release in both humans and dogs and followed the deepening of mutual relationships, which led to interspecies bonding.”

The fact that wolves, even tame ones, wouldn’t be disposed to lock eyes with humans isn’t surprising. In the wolf world, the bear world, and the primate world, staring at another creature is thought to primarily communicate a threat. (Even locking eyes with a dog may not always be positive. One New Zealand medical journal argued that children may be more likely to be attacked by dogs because they are more likely to maintain eye contact that’s interpreted as aggression.)

But our human eye contact vocabulary is a little more diverse. And as dogs have evolved alongside us, they seem to have picked up some of this silent language.

For more on dog science, check out Science magazine’s coverage. And tweet your #upwardfacingdog pic to @worldscifest and @sciencemagazine to share your puppy dog eyes.

Image: iStock.com/UTurnPix

Comments