Whether the weather in your area’s cooperating or not, Thursday, Mar 20 marks the official first day of spring. This is the spring equinox (Latin for “equal night,” although many places will not see equal days and nights on the actual date of the equinox, thanks to the curvature of the Earth), the official changeover from winter to spring. Because the Earth is tilted on its axis (by 23.4 degrees) relative to the plane of its revolution around the sun, the northern and southern hemispheres of the planet are exposed to a shifting ratio of sunlight over the course of the year. Except for twice a year: at the spring and fall equinoxes.

At each equinox, the Earth is positioned such that its southern and northern hemispheres are equally illuminated by the sun. After Thursday, more and more of the Northern Hemisphere will be exposed to the sun, lengthening northern days (and shortening nights south of the Equator), leading to the next seasonal boundary – the summer solstice (on Saturday, June 21 this year), when the North Pole will be most inclined toward the sun and the southern hemisphere will experience winter.

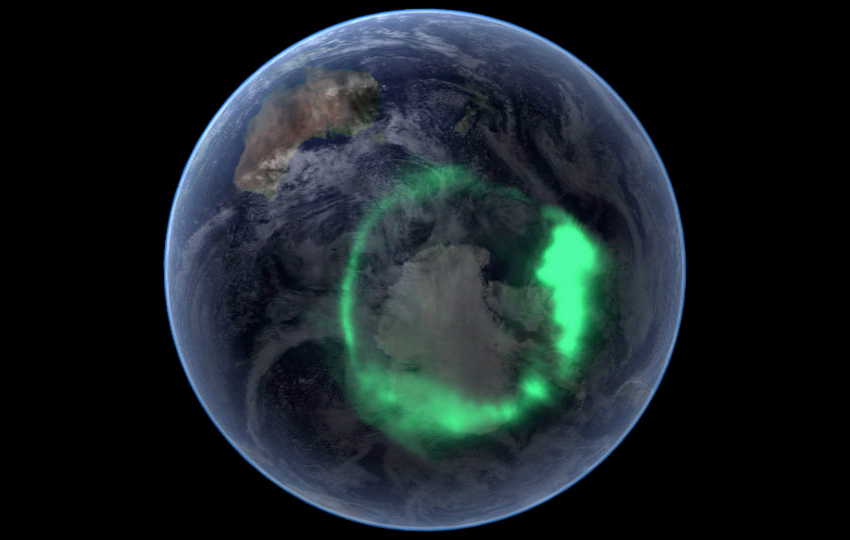

One strange side effect of the equinox is a dramatically increased likelihood of auroras, the magnetic storms that flare like ghostly fire in our atmosphere. The Northern Lights are called Aurora Borealis; the southern counterpart is called Aurora Australis. These storms are caused by collisions between fast-moving electrons (powered by the solar wind streaming off of the sun) and oxygen and nitrogen molecules in our atmosphere. Energized gas molecules give off photons, leading to billions upon billions of little bursts of light, which gives us the hauntingly beautiful auroras that dance in the thermosphere, the second-highest layer of the atmosphere, some 50 miles above the ground.

NASA data shows that geomagnetic disturbances are twice as likely to occur around the equinoxes (March-April), (September-October) than around the solstices. Why? The answer is likely the same reason for the season: axial tilt. For auroras to happen, the Earth’s magnetic field and the magnetic field of the solar wind have to connect just so. Earth’s tilt at the equinoxes appears to orient the planet’s magnetic field in a position that’s ideal for the solar wind pipeline to create these illuminating electron collisions.

Larry Kepko, a researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, compares the phenomenon to using a cup to try and catch water from a sprinkler. If you hold the cup at a certain angle, the water will splash up against the side; if you hold it another way, the water will drop right in.

“If you can tilt the earth such that its magnetic field aligns more with the solar wind magnetic field, you get more of a likelihood of connection,” Kepko told us. “It’s a simple geometrical argument.”

Comments