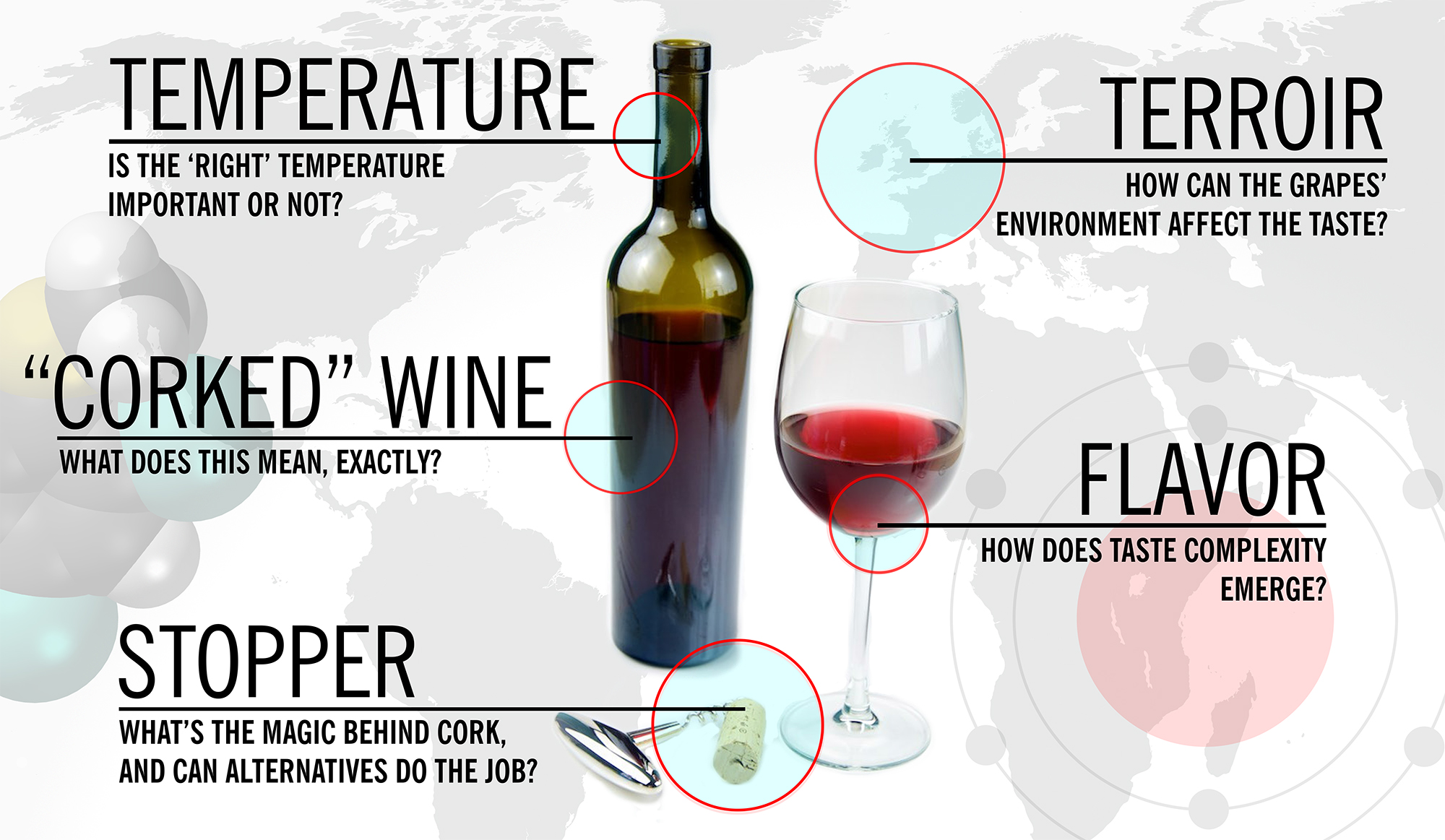

Sorry, Saint Patrick: A recent Yahoo! Shine study discovered that New Year’s Eve is the most popular American drinking holiday. And there’s no better conversation to have, while waiting for the ball to drop, than talking about the wine in your hand. We decided to investigate some of the chemistry of wine, to arm ourselves—and you—with informed answers to common questions about wine.

Even the most novice wine drinker knows you chill white wine, and serve red wine at room temperature…right? Well, from a chemistry standpoint, the temperature itself is far less important than the stability of the temperature. Wine should be stored in a space that can maintain a consistent temperature, roughly 55°F, because fluctuations in temperature cause expansion and contraction. Wine in its bottle contracts and expands much more than the bottle itself; as wine warms, this discrepancy causes the pressure in the bottle to increase, allowing a small amount of the wine’s bouquet (the aromas developed after fermentation) to escape through the cork. When the bottle cools down, the wine contracts more than the glass, causing a vacuum that pulls a greater amount of air in through the cork.

The amount of oxygen wine gets is critically important. When oxygen reacts with alcohol, it creates acetic acid, or vinegar. This can help bring out the woodsy barrel flavors of young wine, but too much oxygen over time will alter the balance, slowly turning your chateauneuf-du-pape to salad dressing. There is clearly a sweet spot for the oxygen-to-wine ratio, and a tool has been developed to measure both the amount of oxygen dissolved in wine and in the space between wine and cork in a bottle. Keep the temperature consistent and this won’t get unbalanced.

Why do we chill white wine before we drink it? Chilling wine brings out its acidity, and white wine tends to have more pronounced acidic flavors—grapefruit, lemon, and green apple, for example. Chilling red wine can accentuate its fruitiness, too, but there’s a problem: Chilling also boosts the flavor contributions of tannins, macromolecules that add bitterness and astringency. Tannins come from grape seeds and skins (as well as from the wood barrels wine is stored in), and red wines have significantly more tannins than white, because whites are typically fermented without the grapes’ skins and seeds (which is why they don’t turn red).

The reason has to do with fermentation. When grapes ferment, yeast eats the natural sugars in the grapes, and the byproducts are carbon dioxide, alcohol, and over 200 aromatic esters (a specific, unique aroma). Our brains construct associations with familiar aromatic esters, because aromas usually come reliably attached to a familiar look, taste, and feel on the tongue. (If you smell eggs, your mind conjures them, you recall their taste and texture.) Many of the esters produced in wine have previously established associations. You can even sometimes love the smell of a wine but not enjoy the taste, if your brain finds a discrepancy between the aromas and the taste/tactile elements of the drink. Because of the sheer load of information—aromas, tastes, sensations—the brain takes in when you sip wine, there are often aromas that novice wine drinkers fail to discern. With practice, a sommelier can retrain her brain to have different associations, and to pick up these more subtle aromas.

A wine from a particular place expresses characteristics related to the physical environment in which the grapes are grown; this is why wine stores sort by region. But it’s actually much more specific than that, and factors ranging from rainfall and weather to soil conditions to anything else that happens while the grapes are on the vine can have a profound effect on the flavor characteristics of the wine.

This is called “terroir,” the complete natural environment in which a wine is produced, including factors such as the soil, topography, and climate. It may be the most overused, under-qualified word of wine connoisseurs, not least because the combination of factors that make-up the terroir, and the relative impact on the wine, is not fully understood.

For instance, soil: there is a good amount of debate as to how soil affects wine, but it is clear there is a connection. Soil in South Africa—very, very old and granite-rich—has been known to reduce the acidity of high-acid wine grapes. The wines produced in these regions have been described as gravelly, hinting-at-graphite. Somehow the soil is impressing its characteristics on the final product, like a tea bag for water passing through en route to the vines’ roots.

Climate’s impact on wine is the same as any other harvested produce: warmer climates produce a riper fruit. As a grape ripens, the amount of sugar it has increases and the perception of its acidity decreases. This does not mean that wine produced in warmer climates will be sweeter—it means that when fermentation begins, the yeast will have more sugar to eat. When the yeast is done, there will be more alcohol in the wine and less acidity in its taste.

Let’s start with what it doesn’t mean. It doesn’t mean the wine’s been “oxidized,” or exposed to too much oxygen, causing the chemical make up of the wine to break down. It also doesn’t mean the cork has dried out and crumbled into the wine. It’s a very specific situation: the presence of a compound created when a fungus commonly found in cork comes in contact with chemicals commonly found in wine production facilities.

Cork is a natural product, and contains natural fungi. When this fungus comes in contact with any of several chlorides common in cleaning solutions wineries use, it can create a compound called 2,4,6-trichloranisole (nicknamed TCA), and the wine is corked. Worse, that bottle can infect other bottles, wiping out a whole wine cellar with “cork taint,” which is not dangerous, except to the finances of the wine-cellar owner. Wineries have begun phasing out the cleaning solutions that can lead to this “cork taint,” and the problem seems to be receding.

Corked wine smells moldy and tastes astringent and fruit-less. You can’t tell if a wine is corked by smelling the cork, though—some really funky corks have held delicious wine underneath. You will know when you’ve tasted a corked wine, however; the taste has been described as “…wet or rotten cardboard.”

There’s a lot of debate in realm of wine closures, among purists who will only go with cork from a cork tree, centrists who will accept synthetic stoppers but never a screw top, and those who say, “Just open it already!” Cork, the ancient standby, is the most expensive to produce and most vulnerable to damage (including the “corked” problem above), but synthetic corks were, and to a lesser degree are, viewed with skepticism.

A big complaint of synthetic cork is that it doesn’t expand and contract like real cork, and thus cannot distribute the small amount of oxygen that wine requires as it ages. Improvements in the thermoplastic used in synthetic corks have been made to address this, though, and producers have even worked on recreating that oh-so-pleasing pop sound that occurs when opening a traditional cork bottle.

Screw tops have long been considered a hallmark of cheap wine, because they completely seal out air, negating the oxygen flow required for aging, and wines that don’t need to age are generally cheaper. Recent innovation has brought screw tops that have a greater amount of permeability, and allow air in at rates comparable to corks, and are beginning to top some very nice bottles of wine indeed.

Enter science, to settle the debate and provide consensus. Last year, wine chemist and UC Davis Professor Andrew Waterhouse began a study of 600 bottles of Sauvignon Blanc with the three closure types. The study will monitor changes in the wine during aging, culminating in a sensory evaluation to determine if wine experts and consumers can taste the different levels of oxidation that occur in the wine due to the type of closure. We’re anxiously awaiting the results…and wondering where we can sign up for studies like this.

Comments