MicroMappers, an innovative app that matches people in need during humanitarian crises to those who deliver aid, was deployed with great success following Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. The app, which relies on the public to tag tweets, was used by hundreds of volunteers around the world over the course of a few days to help the UN identify and map out areas in most need of humanitarian aid. MicroMappers, led by Patrick Meier from the Qatar Computer Research Institute (QCRI), was developed during Science Hack Day NYC, a collaboration between the World Science Festival and the NYU Interactive Telecommunications Program.

MicroMappers, as it exists today, had its beginnings late 2012 when the Standby Volunteer Task Force (SBTF) was tasked by the UN Office of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) to sort through over 20,000 tweets about Typhoon Pablo, which also struck the Philippines. To sort through the thousands of tweets, Patrick Meier and his team at SBTF used the free open-source crowdsourcing and microtasking platform, PyBossa. PyBossa turned out to be an excellent platform for asking volunteers to sort through thousands of tweets, and with this in mind, Patrick came to the Science Hack Day with the idea to build MicroMappers.

Built on the PyBossa platform and hosted by crowdcrafting.org, MicroMappers provides a set of microtasking apps specifically customized for digital humanitarian response. Each individual app asks volunteers to participate in specific tasks. Usually these tasks involve the human cognitive skills that computer algorithms lack,. For example: does this tweet contain relevant and useful information for relief workers in the Philippines? Since this task takes a couple of seconds for a human to solve, and the computer can quickly deliver tweets to many users, MicroMappers, allows for the rapid sorting and categorizing of information that can be very useful to humanitarian aid workers.

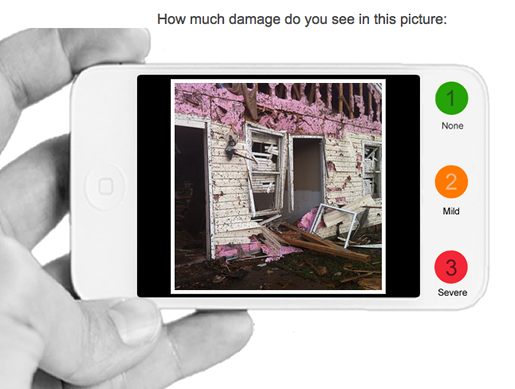

During Science Hack Day NYC, Ariba Jahan, Christine Jackson, and I, helped Patrick develop the early prototype for MicroMappers. We were able to test the prototype with very real data since about a week or two before the hack day, a set of powerful tornadoes struck Moore, OK leaving widespread damage. We used a dataset of 15,000 Oklahoma tornado-related tweets containing Instagram pictures and created an “ImageClicker,” an app that asked users to classify the amount of damage displayed in the picture shown.

Before we loaded the data onto MicroMappers, we made sure to filter out the tweets that we could algorithmically determine to be irrelevant and useless. We took out retweets, broken links, tweets that were not geotagged, and tweets that were geotagged to a location outside of Oklahoma City. This reduced the amount of tweets to a little over 1,000. After we completed the app and loaded the tweets, we tried it out to see what kind of results we could get. We noticed how quickly we were able to sort through the photos. (I timed myself at 50 pictures per minute.) In a matter of a few minutes, we tagged a hefty sample of Instagram photos and were able to identify about 160 pictures of severe damage. We mapped them out using CartoDB and were able to produce the map below.

As you can see, a lot of the pictures were taken around the actual damaged area in Moore (the cluster of dots between Norman and Oklahoma City). Because Tornados leave very recognizable paths, we were able to see how well we were matching the picture locations with the actual damage. The scattered dots located in non-damaged areas brought up the possibility that some people might be taking pictures and uploading them after they have left the damaged area.

Building with PyBossa turned out to be very useful, and not only for MicroMappers. PyBossa’s lead developer, Daniel Lombraña González, was also present at the hack day and helped out in the several projects that utilized the platform.

After the 2 day hack, MicroMappers continued to be developed, and with the help of Ariba, Christine, Daniel, and Ji Lucas, MicroMappers was activated publicly (as a beta test) during the September earthquake in Pakistan. During the course of about 40 hours, MicroMappers received the help from 109 volunteers to tag around 30,000 tweets. While the site and platform functioned well, the results from this early test brought up a lot of issues on the quality of information extracted from the tweets.

Patrick Meier writes that this might be due to the remoteness of the location and its very light social media footprint, unlike the tweets that came out of the Philippines. Patrick and his team had intended to launch the site to the public in November. They had not intended, however to launch it in response to a disaster. Earlier this month, Typhoon Yolanda made landfall in the Philippines, and much like the last year, left a tremendous amount of damage. Once again, MicroMappers was activated. During the first 48 hours after the typhoon made landfall, 230,000 tweets were collected. The tweets were algorithmically filtered for relevancy and 30,000 tweets and 5,000 images were uploaded onto MicroMappers in two apps: TweetClicker and ImageClicker. The first app asked volunteers to identify tweets with useful information for disaster responders, and the second app asked participants to rate the level of damage shown in a picture. Over the next five days, MicroMappers received 105,000 total clicks. (Tweets are repeated on different users to ensure consistent answers.) Ultimately, the five-day volunteer effort produced 600 relevant geolocated tweets and about 180 images published on a live crisis map. The response by volunteers was so overwhelming that the Crowdcrafting server had a hard time keeping up (that’s a good sign!).

Patrick will be the first to admit that the digital humanitarian operations he has organized through MicroMappers are not perfect. “This means that we’re learning (a lot) by doing (a lot),” he says. “Such is the nature of innovation.” As for me, I’m very proud to have been able to be part of the team that originally put MicroMappers together and I know that each time the site gets deployed, it will get better and better at providing crucial information for disaster responders.

To read more about MicroMappers and digital humanitarian response, visit Patrick Meier’s website.

Comments